‘Blanqui’s life was itself a creation, and his only doctrine: Blanqui was the political manifestation of the French Revolution in the nineteenth century’ (Alan Spitzer).1

‘Antiquity attributed to Hercules every great heroic feat; the reactionaries see in me the personification of every crime and every atrocity’ (Blanqui, 1849).2

‘The duty of a revolutionary is always to struggle, to struggle no matter what, to struggle to extinction’ (Blanqui, 1868).3

| 1804 | Napoleon is crowned emperor |

| 1805 | 8 February: Louis-Auguste Blanqui is born in the small provincial town of Puget-Théniers, in the south-eastern department of the Alpes Maritimes, about 50 kilometres north of Nice, on the border with Italy. His father Jean Dominique Blanqui had served as a Girondin member of the Constituent Assembly in 1792-93, and was later appointed sub-prefect of the department by Napoleon, in 1800. His mother Sophie (de Brionville) will remain a staunch source of moral and material support for Blanqui until her death in 1858. She has a total of ten children, two of whom die in childbirth. Blanqui’s older brother Jérôme-Adolphe Blanqui becomes a well-known liberal economist, a disciple of Jean-Baptiste Say, and an influential advocate of free trade. |

| 1814/15 |

Napoleon is forced to abdicate; Louis XVIII is proclaimed king, and rules in accordance with a highly conservative Charter. Through to 1830, the government will be dominated by the so-called ‘Ultra-royalist’ grouping of reactionary aristocrats. The right to vote is restricted to the wealthiest property owners, around 1% of the population. Blanqui’s father is dismissed from his post, and the young Auguste is scarred by the far-reaching ‘réaction blanche’ and the memory of the arrogant foreign troops who occupy post-Napoleonic France. Writing in the third person, he will recall the military occupation as the beginning of his ‘declaration of war upon all factions that represent the past […]. The spectacle of the acts of violence [against the local population] had a profound effect on him, and decided the course of his whole life.’4 The family is saved from destitution when Sophie inherits a somewhat dilapidated estate, the chateau de Grand Mont, in Aunay-sous-Auneau, south-west of Paris, but reckless spending keeps them in a precarious financial position. |

| 1818 | Aged 13, thanks to his older brother Adolphe’s urging and efforts, Auguste Blanqui is sent to Paris to enrol as a boarder at the Institution Massin, and quickly gains a reputation as an exceptionally brilliant student. Adolphe sends their father an enthusiastic letter: ‘One day this child will astonish the world!’5 Well-versed in the classics, Auguste completes his secondary education at the lycée Charlemagne, where he will graduate in 1824. |

| 1821 | Greek war of independence from the Ottoman Empire begins (ends 1830). |

| 1822 | September: aged 17, Blanqui witnesses the execution in Paris of four seditious soldiers, the ‘quatre sergents de la Rochelle’, all members of the secret society La Charbonnerie (the French offshoot of the Italian Carbonari). They are guillotined in front of a large crowd, and face death with striking courage. Blanqui’s biographers sometimes date the beginning of his political commitments from this decisive moment.6 He will remember them later as four ‘martyrs to Liberty’.7 |

| 1824 |

September: Charles X (formerly the comte d’Artois, an arch-reactionary figure in the anti-revolutionary émigré community of the 1790s) becomes king, and moves the government in a still more conservative direction. Increasingly hostile to the repressive and reactionary character of the Restoration regime, as soon as he leaves secondary school Blanqui himself pledges allegiance to the Charbonnerie, which for him will remain a model of genuine political commitment and organisation.8 Unable to find employment in Paris, he works for two years as a tutor in the family of a general Jean Dominique Compans, a veteran of Napoleon’s campaigns, at the château de Blagnac, in the Garonne, 1824-26. By now he has become a strict vegetarian and teetotaller, and his hosts are struck by his ascetic lifestyle.9 |

| 1825 | Charles X’s prime minister Jean-Baptiste de Villèle decrees the Anti-Sacrilege Act. |

| 1826 | Blanqui begins to study both law and medicine at the Sorbonne. |

| 1827 | Blanqui is seriously wounded during clashes with government troops in April and May, and then almost killed on 29 November by a bullet wound to the neck during further protests around the rue Saint-Denis, in Paris. In a short autobiographical sketch10 written decades later he will remember the protest of 29 November 1827 as the day when ‘he rediscovered the people [peuple] of the first Revolution, with their heroic rags, their bare arms [bras nus], their improvised weapons, their indomitable courage and their irresistible anger’; ‘abandoned by the liberal leaders’ of the day, however, the people is soon ‘forced to retreat’ and to give up on what remains an unequal struggle.11 |

| 1828 | Blanqui and a friend travel on foot through the Alps and through southern France (perhaps planning a trip to Greece to support the war for independence), but the association of his family name with the first Revolution leads to his arrest in Nice, and a first brief experience of prison. Upon his release he travels on to Spain, where he finds further reasons to despise the Catholic church. |

| 1829 | Once he returns to Paris, Blanqui begins working as a stenographer with Le Globe (1824-32), a prominent liberal newspaper associated with moderate opposition to the régime, edited by the Saint-Simonian Pierre Leroux and Paul-François Dubois.12 |

| 1830 – July |

After Charles X resorts to increasingly authoritarian means of government, the unexpected ‘three glorious days’ (27-29 July) of the July Revolution lead to his sudden abdication. Soon afterwards the so-called ‘July Monarchy’ is established, with Louis-Philippe (son of the former Duke d’Orléans) as a constitutional monarch set up to defend the interests of property and finance. The new government will be dominated by bankers and financiers like Casimir Périer, and then in the 1840s by François Guizot. Blanqui joins a radical republican group, the Conspiration La Fayette, which helps prepare for the outbreak of revolution in July. He plays a forceful role at every stage of the July insurrection, after predicting on Monday 26 July, to the alarm of Victor Cousin and his Globe colleagues, that ‘before the week is over, it will all be settled by bullets.’13 He is struck by the timid indecision of his Globe colleagues. Once the fighting begins he repeats (according to his recollection) that ‘arms will decide: as for me, I am going to take up a rifle and don the tricolour cockade.’14 He will later claim that he was the first to bring a loaded rifle into the streets during the July days, and for his role on the front lines of the insurrection he was subsequently awarded the ‘Decoration of July’ by Louis Philippe’s new ministry – as Alan Spitzer notes, ‘this was the last award, aside from prison sentences, that he was ever to receive from the French government.’15 |

| 1830 – autumn | Blanqui emerges as one of the most forceful figures who denounce the counter-revolution that immediately follows the July days. In the wake of July, he joins the loose political group La Société des Amis du Peuple (the ‘Friends of the People’), along with other militant conspirators or veteran Carbonari like Philippe Buonarroti, François-Vincent Raspail, and Armand Barbès, as well as the mathematician Évariste Galois and the journalist Godefroy Cavaignac.16 Bernstein estimates its membership at ‘between four and six hundred, but three or four times as many went to its meetings.’17 |

| 1831 |

November: first insurrection of the Canuts, in Lyon. Blanqui plays a prominent role in radical student circles, and in January, on behalf of an improvised ‘Comité des Ecoles’, he drafts a seditious manifesto.18 After further student demonstrations he is arrested for the first time in late January, and imprisoned for three weeks in La Grande Force. Released in February, he returns to violent protest and in July is again arrested and charged, along with fourteen other members of the Société des Amis du Peuple (including Raspail, Antony Thouret, and Aloysius Huber) for plotting against the state, and for press violations. |

| 1832 – January | 10-12 January, ‘Le Procès des Quinze’ [the trial of the fifteen]: Blanqui is tried for the first time, at the Cour d’Assises. Asked to declare his profession, he replies: ‘proletarian […], the profession of thirty million Frenchmen who live by their labour and who are deprived of political rights.’19 In his defence he makes an incendiary and unapologetic revolutionary speech, defying his judges, defending socialist principles, and describing the prevailing situation as a ‘war between the rich and the poor’. The public galleries respond with ‘long applause’, cut short by order of the court.20 Though acquitted by the jury he is condemned by the judge for trying ‘to disturb the public peace by arousing the contempt and hatred of the citizenry against several classes of people which he has variously designated as the privileged rich or the bourgeoisie,’ and in particular for insisting that ‘the privileged live fat off the sweat of the poor’.21 He is sentenced to a year in prison. |

| 1832 |

5-6 June: June Rebellion. Street battles spread across large parts of Paris, led in part by conspiratorial secret societies, and are quelled by 40,000 troops, with a total of around 800 casualties. Charles Fourier founds the journal, La Réforme industrielle ou Le Phalanstère; Etienne Cabet publishes L’Histoire de la révolution de 1830. In February, Blanqui publishes a substantial and incisive ‘Report to the Société des Amis du Peuple’, which tries to make sense of the way popular victory in July 1830 was so easily confiscated by the bourgeoisie. Heinrich Heine hears Blanqui present this report to the Société, and is impressed by his revolutionary vitality, his ‘vigour, candour and wrath’.22 March: Blanqui begins to serve his prison term in Sainte Pélagie (Paris); his health rapidly deteriorates. |

| 1833 |

June: passage of the Loi Guizot, on primary education. Once released, Blanqui returns to neo-Carbonarist forms of clandestine political organising, and lays the foundations for what becomes, in July 1834, the conspiratorial Société des Familles.23 Composed of small isolated groups of militants linked only by a vertical and unilateral chain of command, the group is sustained by an absolute commitment to secrecy, discipline and fraternity. Blanqui and Barbès become its two leading figures, with Blanqui its commander in chief. |

| 1834 |

February: legislation is passed to limit freedom of the press and of association. April: large-scale but uncoordinated riots (a second Canut revolt) break out all over France, notably in Lyons on 9 April and then Paris on 13-14 April. Last-stand barricades around the Rue Transnonain are stormed and many local residents are cut down with astonishing brutality; some children and elderly people are bayoneted in their beds. Hundreds of insurgents are killed and legal proceedings against thousands of others drag on over the next eighteen months. February: Publication of the first and only issue of Le Libérateur: Journal des opprimés, which is entirely written by Blanqui. Recognising the persistence of an age-old struggle of ‘the oppressed against the oppressors’, Blanqui affirms the revolutionary principle of equality, in line with Rousseau and Robespierre. A second issue is prepared but never published, in which Blanqui provides a searing attack on the exploitation of the poor by the rich, and on the forms of cultivated ignorance or mis-education that make such exploitation sustainable. Blanqui argues against participation in the poorly planned and impulsive uprisings of April 1834. 14 August: Blanqui marries Amélie-Suzanne Serre (b. 1814), his fiancé of several years and one of his former pupils, against the wishes of her parents. The couple has only one child, their son Estève (1834-1884), whom they nickname Romeo; a second son is born in 1835 but dies in childbirth. Blanqui is a devoted husband, but his marriage will only last seven years. |

| 1835 |

28 July 1835, Giuseppe Fieschi tries to assassinate Louis-Philippe, and thereby triggers a new wave of police repression and infiltration of conspiratorial groups, targeting the Société des Familles in particular.24 The Société des Familles grows in size and strength in response to government repression, and recruits around 1200 adherents, drawn from a wide variety of social backgrounds (artisans, workers, students, merchants, shop-keepers). Members of the Familles covertly begin to stockpile weapons and to manufacture gunpowder in a workshop at 113 rue de Lourcine. With Louis-Ambroise Hadot-Desages, Blanqui organises a series of pamphlets to facilitate mass political education, under the title Propagande démocratique; three short texts are published. |

| 1836 |

Adolphe Thiers forms his first ministry. 10 March: L’Affaire des poudres. After police are tipped off by an informer, the Familles’ gunpowder operation is shut down by police, and three days later Blanqui is arrested at the house of his associate Armand Barbès, where incriminating membership lists are discovered.24 In August he is convicted along with other members of the Société des Familles for illegal possession of arms and the manufacture of gunpowder. The organisation disintegrates, and Blanqui spends eight months in prison at Fontrevaud, near Saumur. Amélie’s health begins to deteriorate. |

| 1837 | May: an amnesty occasioned by the wedding of Louis-Philippe’s heir allows Blanqui to live quietly in the village of Gency, near Pontoise, albeit under constant police surveillance. Nevertheless he soon begins to reorganise, cautiously and laboriously, former members of the Société des Familles into a new Société des Saisons, which he will again lead along with Barbès and Martin Bernard. Limited almost entirely to Paris, ‘the strength of the Society was put at six or seven hundred in 1838, and at nine hundred in March 1839.’26 With a large working class contingent among the members, the Saisons are sometimes described as a ‘prefiguration of the dictatorship of the proletariat.’27 |

| 1839 |

Louis Blanc publishes L’Organisation du travail. Growing popular discontent forces Louis-Philippe’s conservative prime minister Count Molé to resign on 31 March, and it takes months to find a viable replacement. 12 May: during a prolonged period of economic crisis and political uncertainty, and after careful strategic planning, Blanqui leads, along with Barbès and Martin Bernard, around 500 members of the Société des Saisons and a few partisans of the German-based League of the Just in an armed insurrection. Although the insurgents briefly occupy the Palais de Justice and then the Hotel de Ville they prove unable to storm the main police station. Around a dozen barricades are erected by residents of the faubourgs Saint-Denis and Saint-Martin but the profound secrecy that had surrounded preparations for the insurrection also discouraged the sort of spontaneous popular support upon which its success depended, with both the government and the wider population caught off guard. Once government forces rally, the insurgents are forced to scatter after two days of fighting, with another last stand in and around the rue Transnonain. Around 100 people are killed, including 30 soldiers; 200 people are arrested. Barbès was shot in the head at Blanqui’s side, but survives and is captured, as is Martin Bernard shortly afterwards.28 Blanqui himself escapes immediate capture and lives in hiding for five months, but is tracked down and arrested on 13 October; some critics accuse him of cowardice and indecision. |

| 1840 |

13 January: Blanqui is put on trial with thirty other defendants, but breaks silence only to defend his associates, and to invoke the right of insurrection (which is of course rejected as illegitimate by the judge). The prosecution presents its case over six days; Blanqui refuses all defence, and confounds the large audience by insisting that he had ‘absolutely nothing’ to say.29 He is condemned to death on 31 January, although (in keeping with a precedent set by the conviction of Barbès the previous year) the sentence is quickly commuted to life in prison. From 5 February Blanqui is imprisoned in appalling conditions on Mont Saint-Michel, on the coast of lower Normandy, where he is regularly kept in punishment cells designed to break the prisoners’ health.30 Life in prison soon drives some of Blanqui’s fellow inmates to suicide or madness. During the four years that Blanqui will spend in quasi-solitary confinement on Mont Saint-Michel he writes thousands of pages of notes, which are all destroyed by his mother (to avoid further risk of prosecution) in the late 1850s. |

| 1841 |

31 January: Blanqui’s wife Amélie-Suzanne dies, of a ‘maladie du coeur’, at the age of 26; Blanqui is heart-broken and never remarries. ‘Among my comrades’, he will recall a few years later, ‘who has been forced to drink so deeply from the cup of anguish?’31 In his absence, his son Estève is raised by Amélie’s parents according to Orléaniste principles antithetical to Blanqui, and the two never become close. Locked in a constant war of wills with the prison’s director Theurier, Blanqui observes that ‘when one is crushed by force, one must of course die when they kill you; but to submit willingly to humiliating measures when one can avoid them by making sacrifices, however great these might be, is a precedent that political prisoners must never establish.’32 |

| 1842 |

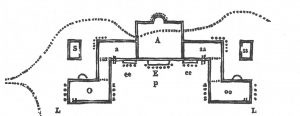

Eugène Sue publishes Les Mystères de Paris. 10 February: pushed to desperate measures, Blanqui, Barbès, Bernard and Hubert try to escape, assisted by a trustworthy associate (Fulgence Girard, now working as a lawyer in nearby Avranches) and by Blanqui’s mother Sophie, who smuggles in small saws and chisels. The prisoners slowly manage to tunnel through the chimneys that separate their rooms, and finally escape at night through Hubert’s window. They nearly succeed in abseiling down the sheer cliff known as the ‘saut Gauthier’ but their rope isn’t long enough for the final stretch of the descent, and after Barbès falls and is injured the four escapees are re-captured and returned to an even stricter régime.33 |

| 1844 | March: finally diagnosed by the prison doctors as terminally ill, Blanqui is transferred to a high security hospital/hospice in Tours. An increasingly liberal and influential press, notably the prominent opposition journal La Réforme (edited by Ledru-Rollin), begins to campaign vigorously for his release, and in December he is offered a qualified pardon on health grounds. Blanqui refuses it however, preferring to maintain ‘complete solidarity with my associates’, and thereby remains in captivity until 1847. His refusal is widely publicised, and further contributes to his growing fame in opposition circles.34 In October 1845 he is able to get out of bed for the first time in twenty months. |

| 1846 |

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon publishes La Philosophie de la misère; Karl Marx responds a year later with his damning Poverty of Philosophy. Blanqui partially recovers his health in Tours, but is charged with helping to incite bread riots that had broken out in the city. The trial takes place in Blois, 26-29 April; he is acquitted, and returned to the prison hospital. |

| 1847 | Alphonse Lamartine publishes his Histoire des Girondins, and Jules Michelet publishes the first volume of his Histoire de la Révolution française. |

| 1848 – February |

22-24 February: a massive insurrection in Paris leads to the sudden abdication of Louis-Philippe. A Provisional Governing Council is hastily established, dominated by Alphonse de Lamartine and Alexandre Ledru-Rollin. On 25 February, a forceful demonstration, led by François-Vincent Raspail, imposes immediate declaration of the Second Republic. Suddenly free to travel as a result of the February uprising, Blanqui arrives in Paris the evening of 24 February and immediately becomes the chief spokesman for positions on the far left of the revolutionary spectrum. On 25 February he defends the red flag associated with socialism against the tricolour inherited from the compromised July Monarchy of 1830-48, and opposes the various compromises offered by Lamartine and other moderate or conservative figures in the new ministry.35 In the last days of February, Blanqui, together with Cabet’s former associate Théodore Dézamy, creates the radical political club, the Société républicaine centrale (soon to be dubbed ‘le Club Blanqui’), rue Bergère, in order to maintain revolutionary pressure on the government.36 |

| 1848 – March |

2 March: universal male suffrage is enacted, and legislative elections are initially planned for 9 April. Many new newspapers and political clubs are established. No longer obliged to work in secret, in the spring of 1848 Blanqui eschews conspiratorial tactics in favour of public debate and the mobilisation of public opinion and mass pressure. ‘Abandon the men of the Hôtel de Ville to their own helplessness’, he recommends, ‘for their power is merely ephemeral. We however have the people and the clubs through which we shall organise them in a revolutionary way, as the Jacobins did.’ He urges patience, and discourages any premature attempt at a coup d’état; what is required is another 10 August 1792, based on massive levels of popular support.37 All through March, Blanqui repeatedly urges the provisional government to postpone the planned legislative elections, so as to allow pro-Republican voices to gain more influence in the provinces and in the countryside, where opinion remains largely shaped by the traditional influence of the local aristocracy and the church. 17 March: Blanqui leads a crowd of around 100,000 to pressure the government to reverse the recent build-up of troops in Paris and to delay the elections; the Provisional Council agrees to postpone them only by a couple of weeks, until 23 April. Unity among the more radical republican groups begins to fray. |

| 1848 – April |

23 April; as Blanqui had predicted, the hastily organised election results strengthen the position of moderate and conservative figures in the new Republican leadership. 26-27 April: workers’ protests in Rouen are violently suppressed by government troops, with dozens killed. Threatened by Blanqui’s growing influence, the provisional government resorts to calumny in order to undermine his reputation in radical republican circles. On 31 March an apparently incriminating document is produced, out of the blue, by Jules Taschereau, a compliant lawyer and official; entitled ‘Déclaration faite par xxx devant le ministre de l’intérieur’, it purports to be a copy of Blanqui’s denunciation to minister Tanneguy Duchâtel, a few months after the failed insurrection of May 1839, of leading figures of his own secret society, apparently in exchange for a lighter prison sentence. The document is unsigned, and the handwriting is not identified. ‘This attack was all the more unsettling’, notes Alain Decaux, ‘for being so unexpected […]; no-one could have withstood such a blow.’38 Blanqui is both outraged and caught off guard by the accusation and issues an immediate denial, followed by a lengthy rebuttal published two long weeks later, on 14 April, entitled Réponse du citoyen Auguste Blanqui. ‘The cowards! […] They dare to lambast me as a sell-out, someone who has been reduced to the mere husk of a man […], while these former valets of Louis-Philippe, now metamorphosed into brilliant Republican butterflies, flutter about the rooms of the Hôtel de Ville.’ This response is counter-signed by 50 of Blanqui’s associates, and in the Gazette des tribunaux another 400 former political prisoners simultaneously sign a protest against the attack on his reputation.39 However implausible the charges associated with it, Blanqui’s enemies and rivals, in particular the embittered Barbès and Eugène Lamieussens, will regularly invoke the Taschereau document against him for the rest of his life; Dézamy, Raspail, Cabet, Proudhon and many others side with Blanqui. At the time, Bernstein observes, ‘an earth tremor could not have shaken the public more than had the document […]; the effects of the caricature and distortion defy measurement.’40 In some circles controversy regarding the Taschereau affair continues to this day.41 15 April: Blanqui holds a secret but inconclusive meeting with Lamartine. |

| 1848 – May |

4 May: the newly elected constituent Assembly meets for the first time, and includes only token representation of the working class. 15 May: a mass march on the National Assembly, ostensibly to protest Russia’s oppression of Poland, turns into an abortive attempt to replace the government. After this failure, conservative figures rapidly consolidate their position, and crack down on radical republicans in Paris. 15 May: as popular discontent grows more acute, Blanqui reluctantly participates in a mass invasion of the newly elected Constituent Assembly, but argues against an improvised coup d’état, and declines to join the procession that then sets off to try (unsuccessfully) to take over the Hôtel de Ville and install a new government. Troops loyal to the Assembly arrest several leaders of the demonstration, including Raspail and Leroux, and Blanqui’s associates Benjamin Flotte and Dr. Louis Lacambre. 26 May: Blanqui is tracked down and arrested for his participation in the 15 May march, and is imprisoned at Vincennes. He will remain in prison for the next ten years. |

| 1848 – June |

21-24 June: June Days Uprising. A desperate but poorly organised workers insurrection is ferociously repressed, with thousands killed, and thousand more imprisoned or deported.42 The conservative tenor of the new republic is now firmly established. Reflecting on the June Days catastrophe in the last months of 1848, Blanqui concludes, like Saint-Just before him, that reliance on ‘half-measures’ had fatally weakened the revolutionary movement; only robust socialist measures could offer any contemporary prospect of continuing in the tradition set by 1792-93. |

| 1848 – December |

20 December: Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte is elected president of the republic, winning around 75% of the popular vote. Blanqui writes scathing denunciations of the new ministry. |

| 1849 |

May: legislative elections strengthen the position of the conservative ‘Party of Order’. 7 March, Blanqui is put on trial at in Bourges, along with a dozen other socialist and revolutionary leaders, including Barbès, Raspail, Albert and Louis Blanc. In his defence he reminds the court that he tried to calm the demonstrators of 15 May 1848, and sought to discourage popular recourse to violence. ‘If I had wanted to overthrow the National Assembly, nothing would have been easier; there were 50,000 people at the demonstration. The iron railings would not have stopped us; when the people wills it, railings are like match-sticks. [… But] I knew very well that the majority of Parisians were not disposed to overthrow the Assembly. The National Guard, most of the workers, and of the departments, would have risen up in indignation, and any government improvised on the basis of chance and surprise would not have lasted eight days.’43 2 April: Blanqui is condemned to ten years in prison, and is initially incarcerated in Doullens, in Picardy. Relying largely on Lamartine’s anti-Jacobin Histoire des Girondins (1847), Blanqui begins writing a series of critical notes on Robespierre, accusing him of stifling the revolution, of restoring religion (in the form of the cult of the ‘supreme being’), and of acting like a ‘premature Napoleon’. |

| 1850 |

15 March: after lengthy debate, passage of the reactionary Falloux law, supported by Adolphe Thiers together with Count Montalembert, which gives the Catholic church effective control over all sectors of education. 31 May: the Assembly, led by Thiers, repeals universal suffrage. February: Blanqui vehemently opposes the consolidation of clerical control over primary schools — ‘twenty years of civil war’ would be preferable to a return to the ‘execrable damnation’ of religious orthodoxy, itself a ‘declaration of war against the human species.’44 ‘The coup d’état is approaching’, he predicts. 20 October: Blanqui is transferred, with twenty others, to the crowded and noisy prison of Belle-Ile, on the coast of Brittany, where the total prison population is around 250. Again imprisoned alongside Barbès and many of his supporters, Blanqui proposes that the prisoners hold a sort of trial to determine the truth of the Taschereau affair; after an argument about the terms of discussion, Barbès refuses to participate.45 Taking advantage of the relatively lax conditions in the prison, Blanqui remains in touch with followers abroad, and offers his fellow inmates informal classes in political economy. Meanwhile in London, in the autumn, Blanquist members of the revolutionary exile community (including Emmanuel Barthélemy, Jules Vidil, and Adam, together with the Germans August Willich and Karl Schapper) break with Marx and Engels, and establish a short-lived ‘Central Democratic Committee of Europe’, which issues a manifesto addressed to ‘The democrats of all nations’, dated 16 November.46 |

| 1851 |

2 December: President Bonaparte finally stages the coup Blanqui had long predicted; he dissolves the Chamber, arrests all the party leaders arrested, and convenes a new assembly to extend his term of office for ten years. A subsequent referendum, held on 20-21 December, apparently wins 92% approval. At the request of Barthélemy, Blanqui smuggles out of Belle-Ile a brief ‘Warning to the People’, dated 10 February 1851, intended to serve as a speech or toast at an émigré banquet in London; its uncompromising critique of Louis Blanc and Ledru-Rollin, along with other members of the 1848 Provisional Council, divides opinion among the exile community. Marx reproduced the text in a leaflet published later that month. |

| 1852 |

2 December, a year after his coup, Bonaparte is crowned emperor Napoleon III. June: Blanqui writes his ‘Letter to Maillard’, which circulates widely among republican circles; in it he rejects the evasive political labels associated with democracy, and insists on the primacy of class struggle and affiliation with either the proletariat or the bourgeoisie. He is now established as the dominant figure among the political prisoners in Belle-Ile; once Barbès is set free by Napoleon III, in October 1854, the prison community becomes a more united political force.47 |

| 1853 |

March: France joins Britain and Turkey, in Crimean War against Russia, which ends in 1856. 4 April: A carefully prepared escape attempt from Belle-Ile, together with his cell-neighbour Barthélemy Cazavan, fails when they are betrayed by a fisherman paid to sail them to the mainland.48 |

| 1857 |

Baudelaire publishes Les Fleurs du mal, and Flaubert, Madame Bovary. November: Blanqui along with 30 others is transferred to the prison of Corte, in Corsica. |

| 1858 | Blanqui’s mother Sophie dies; shortly before her death she orders that all of Blanqui’s papers in her possession, including a large number of carefully elaborated manuscripts written in the 1840s, be destroyed. Blanqui is profoundly discouraged by news of this double loss. |

| 1859 |

2 April: Blanqui is transferred again, to the prison of Mascara in Algeria. 16 August 1859: Blanqui is finally liberated, as part of a general amnesty, but is kept under close police surveillance. He finds the political situation in Paris discouraging, and the population apathetic. He concludes that clandestine journalism is the best means to stimulate the renewal of revolutionary enthusiasm, and over the next few months begins to prepare a series of political pamphlets. |

| 1861 |

Napoleon III invades Mexico, and establishes the short-lived Second Mexican Empire; guerrilla resistance forces the French to withdraw in 1866. 10 March, Blanqui’s new venture is cut short on the eve of its first publication, when he is again arrested on charges of conspiracy and sedition. The trial begins on 14 June. ‘Despite twenty-five years in prison you have held the same ideas’, says the judge; ‘Quite so’, Blanqui replies; ‘I shall desire [their triumph] until death.’49 He is condemned to four years in prison, and imprisoned first in the old Conciergerie and then again in Sainte-Pélagie, in Paris, the prison to which he was first condemned back in 1832. Over the next several years in Sainte-Pélagie, thrown together with various other political prisoners, Blanqui gains influence among a new generation of younger activists, ranging from future leaders of the Radical Socialist Party like Georges Clemenceau and Arthur Ranc to more radical followers like Gustave Tridon, Eugène Protot, Paul Lafargue and Charles Longuet.50 |

| 1864 |

Foundation of the International Workingmen’s Association, in London; labour militancy begins to grow in France, with a wave of strikes in 1865 that then continue off and on through to 1870. 12 March: on health grounds, Blanqui is transferred to the Necker Hospital, rue de Sèvres. Blanqui writes (anonymously) the introduction to Tridon’s enthusiastic commemoration of Jacques Hébert and the most uncompromisingly atheist wing of the sans-culotte mobilisation of 1793-94,51 which appears in a context of growing public interest in the radical phase of the French Revolution, indicated by the publication of several new histories and by popular biographies of Marat (by Alfred Bougeart) and of Robespierre (by Ernest Hamel). |

| 1865 |

October: an ambitious International Student Congress, in Liège, is attended by supporters of Blanqui and of Proudhon. 27 August, with help from Cazavan and the students Edmond and Léonce Levrauld, Blanqui escapes from the Necker prison-hospital and goes into exile in Brussels, where he lives mainly in the house of his long-standing friend the physician Louis Watteau. While he is still in hospital, Blanqui and Tridon launch the anti-clerical journal Candide, with financial backing from Louis Lacambre. Blanqui writes under the pseudonym Suzamel (a compressed version of his wife’s first names). Candide publishes 8 issues, with a circulation of around 10,000 copies, before the government censors close it down. Blanqui’s critique of religion as a form of ideology becomes increasing strident over the 1860s. ‘God is the most fatal aberration of the human brain’, he writes in a typical passage from late 1868, and serves only as a means of pacifying the poor and reconciling them to their lot. ‘God is a means of government, a protector of the privileged and a mystifier of the multitude’; materialism is everywhere attacked by the former because it promises ‘deliverance’ to the latter. ‘The proletarians […] should profoundly distrust any emblem that does not clearly state the motto: atheism and materialism.’52 From 1865 through to 1870, a more organised ‘Blanquist party’ begins to take shape, as Le Vieux – the old man – wins over new support in radical student and workers’ circles, recruiting people who would soon play important roles in the Paris Commune of 1871.53 Alongside stalwarts like Gustave Tridon, the new followers include Jules Vallès, Emile Eudes, Théophile Ferré, Ernest Granger, Eugène Protot, and Raoul Rigault. Granger becomes one of his closest confidants, and the eventual custodian of his manuscripts. By late 1868, Bernstein estimates that Blanqui’s organisation had at least 800 committed members.54 |

| 1866 |

First Congress of the International Workingmen’s Association [IWA], in Geneva. After planning to send several emissaries to the IWA’s Geneva conference, at the last minute Blanqui abruptly orders them to abstain, after concluding that the meeting would only serve to strengthen the position of Proudhon’s followers in the International. Around forty of Blanqui’s followers are subsequently arrested, on 7 November, when they meet to discuss the divisions opened up by the conference; in January 1867, Gustave Tridon and Eugène Protot are sentenced to fifteen months in prison. |

| 1867 | Blanqui undertakes several clandestine trips to Paris, to help build up the new clandestine organisation; Rigault (who will become head of police during the 1871 Commune) develops elaborate and effective forms of counter-intelligence and counter-surveillance, to protect the Blanquist group from informers and spies. |

| 1868 |

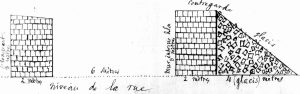

Third Congress of the IWA, in Brussels; a Proudhonist affirmation of cooperatives is eclipsed by a new emphasis on mass industrial action and collective appropriation of the means of production. Blanqui completes and begins to circulate his Instructions for an Armed Uprising, which provides detailed tactical guidelines on everything from the recruitment and organisation of insurgent platoons to the construction of barricades. (Failure to follow these guidelines will once again prove fatal in the final days of the Paris Commune, in May 1871, just as similar failures resulted in similar outcomes, in June 1848, April 1834, and June 1832). Blanqui writes a series of critical notes against positivism and fatalism. Blanqui becomes more sympathetic to the IWA, but remains critical, assuming it would remain diffuse and inconsequential, distant from the Paris proletariat, and a vehicle for ambitious schemers.55 In the autumn of 1868, Blanqui is briefly drawn to Bakunin’s anarchist alternative to the IWA, the short-lived International Alliance of Socialist Democracy, which disbands in June 1869. |

| 1869 |

A general amnesty allows Blanqui to return to Paris. To complement his rejection of fatalism, he writes an extended critique of the spiritualist concept of free will [libre arbitre]. Blanqui and his supporters plan a new weekly newspaper, to be called La Renaissance, which never materialises; its prospectus affirms the ‘dominion of science’ and the principles of ‘justice, equality and solidarity’, along with the ‘rights of labour’. |

| 1870 – January |

12 January, the journalist Victor Noir is killed by prince Pierre Bonaparte, a cousin of Napoleon III, triggering mass protests and strikes. Blanqui helps organise an imposing anti-government demonstration on the day of Victor Noir’s funeral; it is attended by tens of thousands of people, but fails to turn into an actual insurrection. |

| 1870 | 19 July: Beginning of Franco-Prussian War, which immediately goes against France. |

| 1870 – August | 14 August: as the war continues to go badly and popular discontent grows, and pressured by Jules Vallès, Ernest Granger and other hot-headed younger followers, Blanqui reluctantly leads a futile and very hastily arranged attempt at insurrection, which begins with an attempt to take possession of a cache of weapons in a fire station, in the working class neighbourhood of La Villette, near Belleville. The insurgents again hope to attract spontaneous support by setting a decisive example, in the heart of pro-Republican Paris, but the action is poorly planned and poorly attended, and passes largely unnoticed. Acknowledging that the abrupt action had failed ‘to attract a single recruit’, Blanqui disperses the little group of conspirators, and though several are arrested he himself escapes capture.56 The action is widely condemned, not least by more moderate and more conventionally patriotic Republican leaders like Léon Gambetta and Jules Favre, who see it as undermining the French war effort.57 But although the La Villette adventure strikes no immediate popular chord on 14 August, it does nevertheless anticipate the decisive mass uprising that erupts three weeks later, on 4 September. |

| 1870 – September |

2 September, Napoleon III surrenders with 80,000 men at Sedan; in Paris the population begins to take up arms, and to mobilise a new National Guard. 4 September: popular insurrection in Paris leads to the abdication of Napoleon III and establishment of a new Republic and an emergency Government of National Defence; real power however remains mainly in the hands of relatively conservative representatives of the bourgeoisie, notably Jules Ferry, Jules Favre, Jules Simon, and Louis-Antoine Garnier-Pagès, along with the ever-versatile Adolphe Thiers. Napoleon’s appointee as governor of Paris, General Louis-Jules Trochu is named president. 19 September: Prussia’s siege of Paris begins, which eventually ends with the city’s capitulation on 28 January 1871. Tensions soon develop between the mass of the population, who remain determined to resist the Prussian invasion, and a government that is increasingly seen as half-hearted or treacherous. 7 September: Blanqui founds the journal and associated club La Patrie en danger, calling for mass resistance to the German invasion; 89 issues appear over the following months, and the contributors include Gustave Tridon, the Levrauld brothers, Varlet, and Granger. Although very critical of the new and predictably moderate republican leaders, Blanqui initially argues that in the face of so urgent an external threat, national unity should prevail. As his biographers tend to admit, under the pressure of war Blanqui’s own patriotism takes on a decidedly chauvinist if not racist twinge, and by early October he has become unreservedly critical of the emergency government, for failing to prosecute the war with sufficient vigour.58 As the siege of Paris intensifies, Blanqui rails against Trochu’s ineffectual military measures, and his refusal to arm the people at large. |

| 1870 – October |

Adolphe Thiers begins armistice negotiations with Prussia. 31 October: following the surrender of a major part of the French army at Metz, angry crowds converge upon the Hôtel de Ville in Paris and try, unsuccessfully, to establish a new and more militant and responsive government. Blanqui participates in the 31 October uprising, supported by Edouard Vaillant and other new followers, and briefly serves, almost single-handedly, as de facto minister of the interior in the provisional government.59 The hesitant commanders of the National Guard refuse to support the new government, however, and Blanqui is temporarily forced into hiding; Tridon and other supporters are arrested. |

| 1870 – November. |

3 November: a plebiscite in Paris consolidates the position of the interim government, and further marginalises Blanqui and his supporters. With Clemenceau’s support, Blanqui is elected head of the 169th battalion of the National Guard, and calls for mass mobilisation; he is soon removed from his position by Trochu, as tensions rise between the defeatist government and a defiant population. ‘Legitimate power’, Blanqui writes, ‘now belongs to those who are determined to resist. The real voting ballot papers, today, are bullets.’60 |

| 8 December: La Patrie en danger closes, for lack of funds. | |

| 1871 – January |

5 January: the German armies begin to bombard central Paris. Following defeat at the Battle of Le Mans (12 January) and the Battle of St. Quentin (13 January), in late January the Government of National Defence recommends capitulation, and plans for legislative elections to ratify the surrender. President Trochu resigns on 25 January, and is replaced by Jules Favre, who surrenders two days later at Versailles. 21-22 January: Some of Blanqui’s supporters (including Vaillant and Louise Michel) participate in another turbulent but unsuccessful popular insurrection, which is soon dispersed; the government responds with a crackdown on political clubs and popular opposition. |

| 1871 – February |

8 February: conservative and royalist parties prevail in the elections. 17 February: the new parliament elects the conservative and elderly Adolphe Thiers as president, and he signs the peace treaty with Prussia on 26 February, again at Versailles. Exhausted, and disgusted by the government’s lack of patriotic resolve, on 12 February Blanqui leaves Paris to recuperate, bound for Bordeaux. On the same day he publishes the defiant pamphlet ‘One Last Word [Un dernier mot]’, as a final coda to La Patrie en danger. |

| 1871 — March |

18 March: a popular uprising defies government orders to disarm, and leads to the establishment of the Paris Commune, in which followers of Blanqui play a leading role.61 The Thiers government flees in panic to Versailles. 19 March: the Central Committee of the National Guard issues a declaration which proclaims that ‘The proletarians of Paris, amidst the failures and treasons of the ruling classes, have understood that the hour has struck for them to save the situation by taking into their own hands the direction of public affairs.’62 26 March: 92 city councillors are elected in Paris, of which forty-four are classified as ‘neo-Jacobins and Blanquists.’63 17 March: a day before the Commune uprising, Blanqui is captured in Bretenoux, in the department of Lot, at Lacambre’s house. He is condemned by Thiers’ Versailles regime for participation in the 31 October 1870 insurrection, and imprisoned first in Cahors, and then in the Château du Taureau, near Morlaix. 18 March: followers of Blanqui, organised in National Guard units, help lead the rapid seizure of Paris from the regular army. The Blanquists further recommend an immediate march on Versailles, to eliminate the Thiers government and help initiate popular control across the country as a whole; the Commune’s failure to heed this advice will soon seal its fate. 28 March: Blanqui is elected in absentia as honorary president of the Commune. The Communards soon offer to release the 74 hostages (including the president of the high court and the arch-bishop of Paris) that they had taken as leverage against Thiers’ government in Versailles, in exchange for Blanqui’s release; Thiers refuses, recognising that Blanqui on his own was ‘worth a whole army corps.’64 |

| 1871 |

21 May: Versailles troops led by Patrice MacMahon invade Paris, and conquer it after prolonged fighting, one neighbourhood at a time. In a killing spree without precedent in French history they massacre around 25,000 Communards in little more than a week. The reasons for the defeat are accurately predicted in Blanqui’s Instructions for an Armed Uprising (c. 1868) – ‘instructions’ which are largely ignored when the army invades. August: Adolphe Thiers becomes president. The Blanquist party is destroyed as an organised force by the brutal repression in May; Rigault and Emile Duval are killed, Tridon dies soon afterwards in Brussels, and the survivors are forced to flee to London, to other parts of Europe, or to the US. While in prison at Château du Taureau, in conditions of more or less total isolation, Blanqui writes his peculiar exercise in amateur cosmology, Eternity by the Stars, which is published in 1872.65 |

| 1872 |

15-16 February: Blanqui is formally tried for participating in the insurrection of 31 October 1870. In his defence, he argues that ‘I am not here because of 31 October, that is the least of my transgressions. Here I represent the Republic, which finds itself put on trial by supporters of monarchy. The government’s prosecutor has indicted, one after the other, the revolutions of 1789, 1830, 1848, and that of 4 September [1870]; it is in the name of royalist ideas, it is in the name of old rather than new conceptions of law, as he says, that I will be judged here, and it is on these terms that – under your new Republic – I will be condemned.’66 Along with other members of the Commune, Blanqui is duly condemned and sentenced to deportation. The sentence is commuted to imprisonment, on health grounds, and he is transferred on 17 September to the grim prison of Clairvaux, where he spends eight dismal years. Meanwhile Edouard Vaillant rallies some of Blanqui’s supporters abroad, especially in London, and in 1874 they issue a manifesto addressed ‘Aux Communeux’. The 33 signatories include Eudes, Granger, Huguenot, Vaillant, and Varlet. Friedrich Engels subjects the document to close critical scrutiny in an article on the ‘Programme of the Blanquist Refugees of the Commune’;67 this article will serve as the model for later critiques of Blanqui by Second International figures like Kautsky and Luxemburg and, in a more nuanced way, Lenin. |

| 1875 | Marx’s Capital volume 1 is published in French, and is widely read; two years later Jules Guesde and Paul Lafargue found the first Marxist newspaper in France, L’Égalité. |

| 1879 |

Campaigns to offer an amnesty to the surviving Communards grow in strength. 20 April 1879: while still in prison, Blanqui is elected a parliamentary deputy for Bordeaux, following a campaign waged by L’Égalité and a new generation of young radicals. The government declares the result invalid on 1 June, but is finally pressured into releasing the elderly Blanqui from prison, on 10 June. By now he had spent a total of 33 years in prison. Although his health is now broken Blanqui immediately resumes his political and editorial work, and in late November (again with Vaillant, Granger, and Eudes) launches the journal Ni Dieu ni maître, which among other things anticipates a link with a future generation of Russian revolutionaries, by including an article by Pyotr Tkachev and a serialised translation of Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s novel What is to be done? (1863).The phrase ‘No gods, no masters’ will itself be taken up a few decades later as a political slogan in the US, by anarchist and feminist activists. |

| 1800 |

11 July: the government accepts a general amnesty for the Communards, which allows hundreds of people deported to New Caledonia to return to France. Blanqui campaigns in favour of a general amnesty for the surviving Communards, and against the consolidation (in the wake of Napoleon III’s military adventurism and the defeats of 1870) of a large professional standing army. The elderly Blanqui is widely recognised as a principled and influential figure, and in his last eighteen months of life ‘he literally raced over France to speak on his favourite themes: the republic, the standing army, the clerical menace, and amnesty [for the Communards].’68 He publishes the brochure ‘The Army Enslaved and Oppressed.’ |

| 1881 |

1 January, dies of a stroke, aged 75, and is buried in the Père-Lachaise cemetery, in an ornate tomb designed by Jules Dalou; perhaps as many as 100,000 people attend his funeral march.69 At Blanqui’s graveside, the Russian revolutionary activist Pyotr Tkachev lauded his example: ‘To him, to his ideas, to his self-abnegation, to the clarity of his mind, to his clairvoyance, we owe in great measure the progress which daily manifests itself in the Russian revolutionary movement. Yes, it is he who has been our inspiration and our model in the great art of conspiracy. He is the uncontested chief who has filled us with revolutionary faith, the resolution to struggle, the scorn of suffering.’70 |

| Following Blanqui’s death, in 1881 surviving Communards like Edouard Vaillant, Emile Eudes and their allies begin to organise a more formal Blanquist party, the Comité révolutionnaire central. Their manifesto identifies as the chief adversary ‘the capitalist organisation that […] withholds the wealth of society’, and promises to render the nation the genuine ‘master of its wealth and power, and to make every citizen a beneficiary of the one and a participant in the other’.71 Eudes dies in August 1888, and the group soon splits over General Georges Boulanger’s aggressive and anti-Semitic nationalism; growing more sympathetic to Marxian approaches, most of its socialist members eventually join what becomes Parti socialiste révolutionnaire (1898-1901), which itself then merges with the Parti socialiste de France (1902-05), led by Jules Guesde. In the early years of the twentieth century the more reformist Parti socialiste français (1902), grouped around Jean Jaurès, gains influence, and in 1905 most of the French socialist factions finally unite to form the Section française de l’Internationale ouvrière (later renamed to become the current Parti socialiste, in 1969). | |

| 1886 | Jules Vallès publishes the novel L’Insurgé – 1871. |

| 1897 | Gustave Geffroy, a journalist and friend of Georges Clemenceau, publishes L’Enfermé, the first biography of Blanqui. |

- Alan Spitzer, The Revolutionary Theories of Auguste Blanqui, 17, evoking Geffroy, L’Enfermé, 2 volume edition (Paris: Crès, 1926), vol. 2, 218-20. The most detailed and informative biography of Blanqui is Alain Decaux’s Blanqui, L’Insurgé: La Passion de la révolution (1976); the most substantial biography in English is Samuel Bernstein’s Auguste Blanqui and the Art of Insurrection (1971). For further details see the bibliography and list of abbreviations. ↩

- Blanqui, defence speech, in Haute Cour Nationale de justice séant à Bourges, Procès des accusés du 15 mai 1848: Attentat contre l’Assemblée Nationale (Bordeaux: Imprimerie des ouvriers associés, 1849), 723. ‘Un journal de Bourges n’a-t-il pas imprimé, le second jour de ce procès, que ma figure n’avait rien d’humain!’ (723). ↩

- ‘Le devoir d’un révolutionnaire, c’est la lutte toujours, la lutte quand même, la lutte jusqu’à extinction’ (Blanqui, Instructions pour une prise d’armes, MF, 263). Or as Fidel Castro would later put it: ‘El deber de todo revolucionario es hacer la revolucion’. ↩

- Blanqui, ‘Un Homme dont la vie entière…’, MSS 9581, f. 176. ↩

- Cited in Decaux, Blanqui, l’insurgé, 47. ↩

- Geffroy, L’Enfermé (1919 edition), 33; Bernstein, Blanqui, 25-7 Decaux, L’Insurgé, 16-7, 55. ↩

- Blanqui, ‘Un homme dont la vie entière…’, MSS 9581, f. 177. ↩

- Decaux, L’Insurgé, 57-62; cf. Geffroy, L’Enfermé, 35-6; Alan Spitzer, Old Hatreds and Young Hopes: The French Carbonari against the Bourbon Restauration (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1971). ↩

- Decaux, Blanqui, l’insurgé, 66. ↩

- Blanqui, ‘Un Homme dont la vie entière…’ MSS 9581, 175-181 (n.d.); recopied in MSS 9584(2), 225-242. ↩

- Blanqui, ‘Un Homme dont la vie entière…’, MSS 9581, f. 177. ↩

- Cf. Jean-Jacques Goblot, La jeune France libérale: Le Globe et son groupe littéraire 1824-1830 (Paris: Plon, 1995). ↩

- Blanqui, ‘Un Homme dont la vie entière…’, MSS 9581, f. 180; cf. Bernstein, Blanqui, 33; Decaux, L’Insurgé, 90. ↩

- Blanqui MSS 9581, ff. 180-1. ↩

- Spitzer, Blanqui, 5; Decaux, L’Insurgé, 95. ↩

- Cf. Jean-Claude Caron, ‘La Société des Amis du Peuple’, Romantisme 10:28 (1980), 169-79. ↩

- Bernstein, Blanqui and the Art of Insurrection, 46. ↩

- Decaux, L’Insurgé, 107. ↩

- Société des Amis du Peuple, Procès des Quinze ( Paris: Imprimerie de Auguste Mie, 1832), 3. ↩

- Bernstein, Blanqui, 48. ↩

- Société des Amis du Peuple, Procès des Quinze, 148. ↩

- Heinrich Heine, De la France (1856) (Paris, Calmann Lévy, 1884), 59-60; cf. Dommanget, Auguste Blanqui: des origines à la Révolution de 1848, 115-6. ↩

- Bernstein, Blanqui, 70-1; Decaux, L’Insurgé, 168-70. ↩

- Decaux, L’Insurgé, 177-8. ↩

- Decaux, L’Insurgé, 177-8. ↩

- Bernstein, Blanqui, 80. ↩

- Decaux, L’Insurgé, 190-1; for a critique of the comparison between Marx and Blanqui’s conception of such a transitional dictatorship, see in particular Hal Draper, The ‘Dictatorship of the Proletariat’ from Marx to Lenin (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1989). ↩

- Bernstein, Blanqui, 85-97; Decaux, L’Insurgé, 202-206; Dommanget, ‘Auguste Blanqui et l’insurrection du 12 mai 1839’, La Critique Sociale XI (March, 1934), 233-45. ↩

- ‘Procès des Journées de Mai 1839’, in Blanqui, OI, 421; cf. ‘Dialogue avec J.F. Dupont (Blanqui’s lawyer in January 1840), in OI, 407; Decaux, L’Insurgé, 210-1. ↩

- Decaux, L’Insurgé, 220-45; cf. Blanqui, letters to Fulgence Girard, 1840-41, in OI, 423-452; Fulgence Girard, Histoire du Mont Saint-Michel comme prison d’état, avec les correspondances inédites des citoyens: Armand Barbès, Auguste Blanqui (etc.) (Paris: Paul Permain et Cie., 1849); Jill Harsin, Barricades: The War of the Streets in Revolutionary Paris, 1830-1848 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), 233-44. ↩

- Blanqui, ‘Réponse du Citoyen Blanqui’, 1848, cited Decaux, L’Insurgé, 231; cf. Blanqui MSS 9584(1), f. 17ff. ↩

- Blanqui, letter to his mother, 15 September 1841, in OI, 439. ↩

- Decaux, L’Insurgé, 246-51. ↩

- Blanqui, OI, 493-4, 496; cf. Decaux, L’Insurgé, 260-2. ↩

- Cf. Alfred Delvau (secrétaire intime du citoyen Ledru-Rollin), L’Histoire de la Révolution de Février (Paris: Blosse, 1850), 314-23. ↩

- See Suzanne Wasserman, Les Clubs de Barbès et de Blanqui ( Paris: Édouard Cornély, 1913); Peter H. Amann, Revolution and Mass Democracy: The Paris Club Movement in 1848 (Princeton, 1975), 119-22; Patrick Hutton, The Cult of the Revolutionary Tradition: The Blanquists in French Politics, 1864-1893 (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 1981), ch. 2. ↩

- Alphonse Lucas, Les Clubs et les clubistes (Paris, 1851), 214, cited in Bernstein, Blanqui, 140. ↩

- Decaux, L’Insurgé, 320. ↩

- Volguine, ‘Note Biographique’, in Blanqui, Textes choisis, 46. ↩

- Bernstein, Blanqui, 160, 165. ↩

- The most detailed study of the Taschereau affair remains that of Maurice Dommanget, Un Drame politique en 1848 (1948). In an earlier short study, published in 1924, Dommanget initially conceded that Blanqui might have made a confession in 1839, during a rare moment of weakness. In his later and much more substantial analysis, however, he arrives at the opposite conclusion, arguing that the document, written in a style that is not typical of Blanqui, and containing multiple inconsistencies, was a malicious forgery, designed to discredit him and the wider revolutionary movement at a pivotal moment in the early stages of the precarious second Republic. Blanqui’s previous biographers Geffroy and Zévaès likewise argued that he was the victim of an elaborate police fabrication, compounded by the petty resentment of Barbès and his associates (Geoffroy, L’Enfermé, 147-54; 441; Zévaès, Blanqui, 61-3). Samuel Bernstein is ‘convinced by a study of the evidence, that (the document) never existed’; vilification, he notes, would prove more damaging than martyrdom (Bernstein, Blanqui, 107, 158). Geffroy and Dommanget, furthermore, point to evidence which suggests that, if indeed there was an informer, it might have been Lamieussens instead.

Alain Decaux’s biography offers the most recent detailed analysis, and perhaps the most nuanced conclusion (Decaux, Blanqui, l’insurgé, 315-48). He notes Blanqui’s lack of motive, and the lack of reward, and demonstrates at length that the document itself was almost certainly a forged ‘composite’ assembled by the ministry of police, drawing on testimonies gleaned by several different witnesses and informers. However, Decaux speculates that it is also possible that Blanqui might well have sought some sort of meeting with the minister of the interior, Tanneguy Duchâtel, in 1839 – not in order to curry any sort of favour, and without any sense of shame or submission, but on the contrary in order to force a direct confrontation with his main adversary. ‘Blanqui, c’est le conspirateur-né (…). Il a l’orgueil de ses actes, du rang occupé dans les sociétés secrètes. Une fois arrêté, il a pu souhaiter un entretien avec un adversaire, un égal, un ministre. En somme, la négociation au sommet (…). L’erreur de Blanqui, en l’occurrence, c’est de ne pas avoir tenu compte de sa position de faiblesse. C’est de ne pas avoir prévu que l’on pourrait tirer parti contre lui ce ces rencontres – et quel part!’ (Decaux, L’Insurgé, 347).

The idea that Blanqui might have colluded with the police in 1839 certainly seems inconsistent with the whole of Blanqui’s thoroughly unrepentant political life. A few years after the event, Barbès was pardoned and freed by Napoleon III, in October 1854, following a public letter in which Barbès wrote in support of the imperial war effort in the Crimea. ‘Barbès and Blanqui have long shared the real supremacy of revolutionary France’, observed Marx and Engels at the time. ‘Barbès never ceased to calumniate and throw suspicion upon Blanqui as in connivance with the Government. The fact of his letter and of Bonaparte’s order decides the question as to who is the man of the Revolution and who not.’ (Marx and Engels, ‘The Sevastopol Hoax; General News’, The New York Daily Tribune 4215, 21 October 1854, in Collected Works (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1980) vol. 13, 491).

For opposing views, more sympathetic to Barbès, see Jean-François Jeanjean, Armand Barbès (Paris: Édouard Cornély, 1909), I, 159-70, and Maurice Paz, Blanqui: Un Révolutionnaire professionel (1984). ↩

- ‘Alexander Herzen said that the Terror of 1793 had never equalled that of 1848. Paris was depopulated. Many shops could not reopen for lack of skilled hands (…). With the insurgents were interred socialist aspirations and faith in pre-fabricated earthly Edens. For several weeks after the blood-letting, the capital was a ghost city’ (Bernstein, Blanqui, 185). ↩

- Blanqui, defence speech, in Haute Cour Nationale de justice séant à Bourges, Procès des accusés du 15 mai 1848. Attentat contre l’Assemblée Nationale (Bordeaux: Imprimerie des ouvriers associés, 1849), 726-7. ↩

- Blanqui MSS 9581, f.160, f. 92. ↩

- Decaux, L’Insurgé, 423-7. ↩

- The full text is reproduced, with acerbic parenthetical commentary, in Marx’s letter to Engels of 2 December 1850, in Marx and Engels, Collected Works vol. 38 (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1989), 246-7. Cf. Hal Draper, Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution, vol. 3, The ‘Dictatorship of the Proletariat’ (NY: Monthly Review, 1986), 186ff. ↩

- See Dommanget, Auguste Blanqui à Belle-Ile ( Paris: Librairie du Travail, 1935). ↩

- Cf. Bernstein, Blanqui, 236-7. ↩

- Bernstein, Blanqui, 252. ↩

- Arthur Ranc, Souvenirs — Correspondance 1831-1908 ( Paris: Édouard Cornély et Cie., 1913), 27; Paul Lafargue, ‘Auguste Blanqui-souvenirs personnel,’ in La Revolution Française, 20 April 1879. ‘Thus the imperial censors and police assembled in a single prison (La Sainte-Pélagie) much of the literary and political talent of Paris. A kind of informal yet high-grade seminar grew up…’ (Bernstein, Blanqui, 259). ↩

- Gustave Tridon, Les Hébertistes: Plainte contre une calomnie de l’histoire (Paris: (Anon.), 1864). ↩

- Blanqui, ‘Athéisme et spiritualisme’, 4 November 1868, MSS 9592(1), f. 121. ↩

- Dommanget, ‘Les Groupes blanquistes de la fin du Second-Empire’, Revue Socialiste 44 (February 1951), 225-31; Bernstein, Blanqui, 257-9; 282-4. ↩

- Bernstein, Blanqui, 284. ↩

- Blanqui, letter of 14 November 1868, MSS 9591(2), f. 362-3. ↩

- Paz, Blanqui, 210; Decaux, L’Insurgé, 536-42; Bernstein, Blanqui, 314-5. For Blanqui’s own description of this sequence see Blanqui, La Patrie en danger (Paris: Chevalier, 1871), 49-61. ↩

- Decaux, L’Insurgé, 544-5. ↩

- Dommanget, Blanqui et la guerre de 1870-71 et la Commune (Paris: Domat Montchrestien, 1947), 51; Bernstein, Blanqui, 323-4. ↩

- Dommanget, Blanqui, la Guerre de 1870-71 et la Commune, 70-84. ↩

- Blanqui, ‘L’Abdication d’un peuple’, 14 November 1870, La Patrie en danger, 242. ↩

- ‘The role of the Blanquists in the Commune is known to have been significant,’ Spitzer notes, ‘but is also somewhat obscure and subject to various interpretations. It is certain that the Blanquists contributed a great deal to the consolidation of the spontaneous rising that gave birth to the Commune. They became the consistent supporters of vigorous direct action against Versailles, and of many of the acts of violence which marred the dying days of the Commune. The Blanquists did not function as an organized political party and confessed to a sense of confusion and lack of direction which they felt the missing Blanqui would have supplied.’ (Spitzer, Revolutionary Theories, 14). ↩

- For discussion, see Marx, The Civil War in France (1871), chapter 5; Alain Badiou, ‘The Paris Commune: A Political Declaration on Politics’, Polemics (London: Verso, 2012), 272 ff. ↩

- Bernstein, Blanqui, 337. ↩

- Benjamin Flotte, Blanqui et les otages en 1871 (Paris: Imprimerie Jeannette, 1885), 26-7. ↩

- Walter Benjamin would later interpret this short book, with scant justification as a kind of ‘unconditional surrender’; Bernstein reads it as ‘proof of diligent effort to banish himself as far as possible from earth and politics’ Bernstein, Blanqui, 342; cf. Peter Hallward, ‘Blanqui’s Bifurcations’ (2014), and Ian Birchall, ‘Why Did Walter Benjamin Misrepresent Blanqui?’ (2016). ↩

- Cited in Decaux, L’Insurgé, 594. ↩

- Friedrich Engels, ‘Programme of the Blanquist Fugitives from the Paris Commune’ (26 June 1874), in Marx and Engels, Collected Works vol. 24 (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1989), 12-18. Cf. Richard Hunt, The Political Ideas of Marx and Engels, vol. 1: Marxism and Totalitarian Democracy, 1818-50 (London: MacMillan, 1975), 310-2; Draper, Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution, vol. 3: The ‘Dictatorship of the Proletariat’, 302-5. ↩

- Bernstein, Blanqui, 349. ↩

- Geoffroy, L’Enfermé, 437-8; Decaux, L’Insurgé, 625-9. ↩

- Ni Dieu ni maître, 9 January 1881, cited in Spitzer, Revolutionary Theories, 17. ↩

- Ni Dieu ni maître, 24 July 1881, cited in Bernstein, Blanqui, 356. ↩