At odds with followers of Proudhon on the one hand and of Marx on the other, while Blanqui commanded unrivalled authority in French revolutionary circles during parts of his own lifetime he was quickly forgotten after his death, and there has been little searching engagement with his work or legacy since the middle of the twentieth century. Today he is perhaps most often accessed through Walter Benjamin’s rather jaundiced reading of an idiosyncratic late text, Eternity by the Stars (1872) – a text that Benjamin misinterpreted, in the late 1930s, as an apparent act of ‘unconditional surrender’. The eclipse of revolutionary politics over the last few decades has further discouraged detailed study of Blanqui’s work, and such study is also complicated in practice by the fact that the great majority of his writings have survived only as a mass of disorganised manuscript fragments, held at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, which until now have remained effectively inaccessible to a wider public.

Most scholarly discussion of Blanqui in recent decades, such as it is, has tended to embrace as more or less self-evident the critical line adopted by Marx and Engels early in their one-sided debates with Blanquist members of the London exile community, in the late 1840s and 50s. To this day, the dominant interpretation remains that Blanqui offered a merely putchist and conspiratorial approach to political action, that he lacked any genuine understanding of historical context or socio-economic processes, and that he was indifferent to the real work of popular mobilisation, political education, and revolutionary organisation. This line quickly became a matter of broad consensus for almost every leading figure of the Second International, and it has been a standard refrain on all sides of the political spectrum ever since.

This website aims to help rescue Blanqui’s legacy from oblivion. Its purpose is to provide readers with the fullest feasible set of resources for a critical assessment of his work, including almost the whole set of his own writings, newly commissioned analyses of his legacy, and the most inclusive selection of secondary texts that copyright permits. There can be no denying that in many ways Blanqui was very much a man of his time, and needless to say the goal of this site is not to provide uncritical affirmation of all his various positions and perspectives, nor to downplay his sexism or his nationalism, nor the limitations of his approach to political economy; the goal is to restore him to the controversial but significant historical and theoretical place he deserves, and thereby both to broaden and sharpen the terms of contemporary political discussion.

Research Context

Beyond the immediate interest of Blanqui’s incisive approach to themes like insurrection, mass education, and political violence, this website also aims to contribute material to ongoing consideration of a question that was central to Blanqui and many of his associates, but that has generally been dismissed or neglected by many of today’s most influential critical theorists and European philosophers. The question is this: to what extent is political action best understood in terms of the actors’ own deliberation, purpose and resolve, rather than by the purportedly ‘deeper’ logics of e.g. economic development, historical tendency, providential design, technological innovation, cultural differentiation, or unconscious drive?

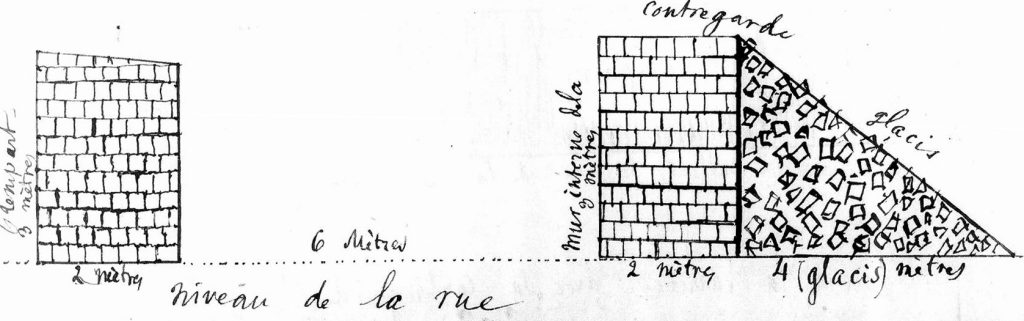

Blanqui’s position on this question is more nuanced than it might sometimes appear, but overall, whether he’s discussing the strategic configuration of a street barricade, or ‘communism as the future of society’, or a Paris-led campaign for popular education, he generally assumes that if it is to prevail and endure, the movement from imposed necessity to an insurgent freedom must itself be freely and consciously undertaken. In keeping with the broad Enlightenment and Jacobin traditions, what is politically decisive is the power of a reasoned common purpose — the preparation, emancipation and mobilisation of a capacity for critical thought directly linked to the exercise of a collective will. Again like Rousseau before him (and Nietzsche or Foucault after him), however, Blanqui rejects any spiritualist or religious appeal to an abstract, metaphysical notion of a disembodied libre arbitre or ‘free will’, a punitive ‘fantasy’ that serves only to assign misplaced moral blame to the victims of social disadvantage.

If la volonté du peuple is not to be confused with an abstract and indeterminate libre arbitre, however, still less is it to be conflated with any sort of all-determining biological inevitability, cultural destiny or historical ‘fate.’ The only legitimate forms of social organisation are those we choose of our own ‘full and free will’, and the only legitimate form of government is one that ‘expresses the enlightened will of the nation’s vast majority.’ At every stage of his work, Blanqui privileges freedom over necessity and transformative ideas over unchangeable ‘facts’ or material constraints. ‘It is ideas alone that make people what they are’, he insists: ‘the instrument that frees us is not our arm but our brain, and the brain lives only through education’ and cultivated practices of critical thinking. By extension, and as if to invert the priorities of Marxian historical materialism, Blanqui believes that ‘philosophy rules the world’ and that ‘the life of a people is not in works of its hands but in what it thinks.’

If la volonté du peuple is not to be confused with an abstract and indeterminate libre arbitre, however, still less is it to be conflated with any sort of all-determining biological inevitability, cultural destiny or historical ‘fate.’ The only legitimate forms of social organisation are those we choose of our own ‘full and free will’, and the only legitimate form of government is one that ‘expresses the enlightened will of the nation’s vast majority.’ At every stage of his work, Blanqui privileges freedom over necessity and transformative ideas over unchangeable ‘facts’ or material constraints. ‘It is ideas alone that make people what they are’, he insists: ‘the instrument that frees us is not our arm but our brain, and the brain lives only through education’ and cultivated practices of critical thinking. By extension, and as if to invert the priorities of Marxian historical materialism, Blanqui believes that ‘philosophy rules the world’ and that ‘the life of a people is not in works of its hands but in what it thinks.’

About the website

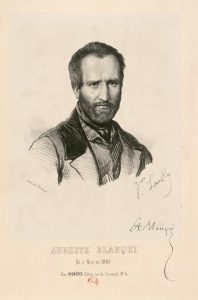

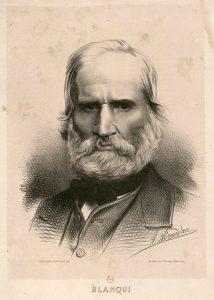

This is the first substantial website to be devoted to Blanqui, in any language. It posts a wide sampling of important texts, both in new English translations and in their original French, some of which are transcribed here for the first time. It provides reproductions of all of Blanqui’s published and posthumously published works, transcripts of the main court proceedings undertaken against him, and scans of the full set of his manuscripts held by the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, along with a detailed chronology and a bibliography. It complements a selection of focused studies of Blanqui with a broad set of critical assessments of his legacy, extracted from writers positioned across the revolutionary spectrum, and includes a collection of maps, portraits, photos and other pertinent images.

This is the first substantial website to be devoted to Blanqui, in any language. It posts a wide sampling of important texts, both in new English translations and in their original French, some of which are transcribed here for the first time. It provides reproductions of all of Blanqui’s published and posthumously published works, transcripts of the main court proceedings undertaken against him, and scans of the full set of his manuscripts held by the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, along with a detailed chronology and a bibliography. It complements a selection of focused studies of Blanqui with a broad set of critical assessments of his legacy, extracted from writers positioned across the revolutionary spectrum, and includes a collection of maps, portraits, photos and other pertinent images.

The site also hosts audio recordings from the first international conference on Blanqui to be held in UK (at Kingston University, in May 2016), as well as recordings from a broader, follow-up conference on ‘The Will of the People’ (at Kingston University, June 2017).

The site was created in 2016 by two researchers in Philosophy at Kingston University, Philippe Le Goff and Peter Hallward. The site was designed by Karl Inglis, and it will be updated on a regular basis by Peter Hallward.

Preparation of this website was made possible by a generous research grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), with support from the Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy (CRMEP) and Kingston University’s Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences.

Last updated: 7 April 2017.